Aimee B. Anderson

I first became acquainted with George Anastaplo in 1981, during my first year of law school at Loyola University of Chicago School of Law, where at that time he taught constitutional law. We students did not know anything much about him (it later turned out that this was also his first year at Loyola); we certainly did not have any idea that he had so vigorously defended the ideals of this country for such a lengthy period of time, at great personal sacrifice and much to the detriment of his legal career. Despite his far-ranging references and the broad reach of the topics discussed with his students, that was a subject that he did not raise in his classes.

Later I came to know him and the events of his life in much greater detail. But even now, I puzzle over what it was in his character, or upbringing, or environment that had provided him so early in life with his finest qualities, qualities that he exhibited to all for the rest of his life: an insatiable curiosity, an unwavering courage, and the rare ability to evaluate the present while in the present. These qualities seem to have been well ingrained within him at an early age, and they informed his actions at every stage of his life.

George Anastaplo was the first of three children, all boys, born to Theodore and Margareta (Syriopoulos) Anastaplo. His parents had been born in the same Greek village, but they first met and married in the United States, probably having arrived here in the early 1920s. George was born in St. Louis on November 7, 1925, into a community that was clearly not fully integrated into the life of this American city: he did not speak English until he attended grade school.[1]

George seems to have been sensitive to the difficulties of his parents’ adjustment to life in the United States, but he clearly saw himself as different from them.[2]

When he was about nine years old, he developed a serious case of diphtheria, so severe that his mother feared he would die. As part of the treatment or recuperation from the illness, George was sent to a type of sanatorium near St. Louis. At about this time, his father, who had apparently suffered some financial losses, decided to move the family to Carterville, a small town in southern Illinois. The rest of the family did move, leaving George behind in St. Louis for some period of time before he was released and joined his family in Carterville. Thus, at a very early period he seems to have been called upon to be self-reliant.

George grew up in Carterville, and his parents spent the rest of their lives there. His father opened a diner (not a Greek restaurant, George would say, since the residents of Carterville in those days would not have eaten Greek food), and George worked there as a boy. He seems to have disliked the experience and remained essentially indifferent to meals and food preparation for the rest of his life.

He was a good student and was encouraged by teachers who were undoubtedly invigorated by his curiosity and intellect. As soon as he finished high school, in 1943, he set about trying to join the Army Air Corps. He was strongly discouraged in this endeavor by the military since he was underweight and apparently had a heart murmur. However, George was persistent, hanging about the air field near town and repeating his attempts to join up, until the officials agreed to take him on as a trial, figuring that he would not be able to complete the training. As in many other circumstances, George was not to be deterred (stubborn, some would call him during his lifetime), and he became a navigator in the Air Corps, an accomplishment that provided him with great pride and a wealth of anecdotes regarding his experiences (some involving great courage and quite a bit of self-reliance) for the rest of his life.

On leaving the Air Corps in 1947, George was eligible for educational benefits under the G.I. bill, and he applied for admission to the University of Chicago.[3] Having been in the service, he was somewhat older than many of the other students, but by 1948 he had finished his undergraduate course work and entered the law school at the University of Chicago.[4] There he was at the top of his class.

In the fall of 1950, his final year of law school, he had taken and passed the Illinois bar exam and was interviewing for a position with one of the downtown Chicago law firms. All that remained before the start of his career was a seemingly routine, perfunctory interview with a panel of the fitness committee of the Illinois Bar, as required of all applicants to practice law. So uneventful did this interview appear to be that George had agreed to have lunch with a friend immediately afterward.

But chance,[5] the climate of the times, and George Anastaplo’s refusal to concede on an issue that he thought vital to a proper view of the rights historically granted to the American people collided, resulting in an eleven-year legal battle that irrevocably changed Anastaplo’s career and touched the lives of innumerable jurists, lawyers, students, and others.

I will merely sketch the outlines of the controversy. The transcripts and court opinions of that lengthy litigation are available and have been summarized elsewhere. While these events give us some insight into the character of George Anastaplo, they do not represent the real value of the man as a scholar and a teacher who deeply influenced the thought and the lives of so many. He did not, I believe, define himself by these events, although some have been tempted to do so.

Anastaplo’s first appearance before the Committee on Character and Fitness of the Illinois Bar took place on November 10, 1950, when he was interviewed by a two-person subcommittee. In that environment of rampant McCarthyism,[6] the members of the subcommittee took umbrage at Anastaplo’s position on the right of revolution (expressed as an almost verbatim quotation from the Declaration of Independence). The interviewers then proceeded to question him as to his membership, or not, in certain political associations, including the Communist party, an inquiry that Anastaplo deemed improper, refusing to answer such questions.

This occasioned a further appearance before the entire Character and Fitness Committee, which took place on January 5, 1951, and the committee ultimately refused to issue the required certificate of satisfactory character and fitness. In 1954 the Illinois Supreme Court required the Committee on Character and Fitness to explain its decision, and on September 23 of that year, it upheld the committee’s decision.[7] In 1955 the United States Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from the decision of the Illinois court, denied the petition for rehearing, and denied Anastaplo’s motion seeking admission to the Supreme Court. The issue would appear to have been finally decided.

In 1957, however, certain U.S. Supreme Court decisions prompted Anastaplo to petition for a rehearing from the Committee on Character and Fitness, and having been ordered by the Illinois Supreme Court to allow this petition, the case began again. Once more the committee refused to certify Anastaplo as having the requisite character,[8] and once more, in 1959, the Illinois Supreme Court refused to reverse that decision. On May 2, 1960, however, the United States Supreme Court agreed to review the Illinois court’s ruling.

On December 14, 1960, the Supreme Court heard Anastaplo, representing himself, in oral argument. The opinion, issued on April 24, 1961, upheld the Illinois decision and also denied Anastaplo’s motion for admission to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Hugo Black, however, wrote a dissent from that 5–4 decision against Anastaplo that has come to be regarded as one of his finest opinions.[9] Pointing out that “from a legal standpoint, [Anastaplo’s] position throughout has been that the First Amendment gave him a right not to disclose his political associations or his religious beliefs to the Committee,” Black recognized the essential character of the man who was asserting this position. He elaborated:

[Anastaplo’s] decision to refuse to disclose these associations and beliefs went much deeper than a bare reliance upon what he considered to be his legal rights. The record shows that his refusal to answer the Committee’s question stemmed primarily from his belief that he had a duty, both to society and to the legal profession, not to submit to the demands of the Committee because he believed that the questions had been asked solely for the purpose of harassing him because he had expressed agreement with the assertion of the right of revolution against an evil government set out in the Declaration of Independence.

Black also pointed out that the committee had had the opportunity to judge Anastaplo’s character for itself during the lengthy hearing process: “Faced with a barrage of sometimes highly provocative and totally irrelevant questions from men openly hostile to his position, Anastaplo invariably responded with all the dignity and restraint attributed to him in the affidavits of his friends.” As to his support of the right of revolution, Black found that

the one and only time in which [Anastaplo] has come into conflict with the Government is when he refused to answer the questions put to him by the Committee about his beliefs and associations. And I think the record clearly shows that conflict resulted, not from any fear on Anastaplo’s part to divulge his own political activities, but from a sincere, and in my judgment correct, conviction that the preservation of this country’s freedom depends upon adherence to our Bill of Rights. The very most that can fairly be said against Anastaplo’s position in this entire matter is that he took too much of the responsibility of preserving that freedom upon himself.

Anastaplo filed a petition for rehearing in the U.S. Supreme Court, which was denied—as he had expected it would be—on October 9, 1961. Thus concluded the litigation; Anastaplo had, as he put it in his petition for rehearing, “practiced all the law he [was] ever going to.” Some correspondence passed between the jurist and the scholar in subsequent years, and Hugo Black’s own funeral service included a reading of an excerpt from his dissenting opinion, which famously concludes with the admonition that “we must not be afraid to be free.”

Despite his having been an excellent student and apparently well-regarded by all, Anastaplo was not supported in his bar committee difficulties by many of those whom he felt should have stood up for him and his position, including the dean and much of the faculty of the law school at the University of Chicago.[10] This was a source of significant disappointment to him, one that he never forgot, although he has, typically, acknowledged the “unanticipated benefits of adversity.”[11]

During the pendency of the litigation, Anastaplo, deprived of the opportunity to practice law, went to work in other capacities. He drove a taxi cab for a period of time, a job that fortuitously brought him into personal contact with Justice Daily, a member of the Illinois Supreme Court who had recently heard Anastaplo’s argument on his first appeal from the bar committee’s refusal to certify him.[12] Justice Daily later led the four-man majority of the Illinois Supreme Court that again upheld the committee in 1959.

In the mid-1950s Anastaplo returned to school and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1964. His dissertation for the Committee on Social Thought ultimately became his book The Constitutionalist.

In 1957 he began his formal teaching career, first in the Basic Program of the University of Chicago, a position he continued to fill until the end of the fall quarter of 2013, just months before his death.[13] He also taught in the political science and philosophy departments at Rosary College, now Dominican University, in River Forest, Illinois, near Chicago. He taught seminars on politics and literature at the University of Dallas for two years, commuting there regularly from Chicago for the classes. Throughout his career he was an invited speaker at a number of academic institutions, and he regularly lectured all over the country.

Anastaplo began teaching constitutional law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law in the fall of 1981, and he continued teaching seminars there on various topics of jurisprudence and constitutional law until the end of the fall semester of 2013. At Loyola, too, Anastaplo’s classes were routinely fully subscribed.

George Anastaplo prided himself on never having missed a class since his grade school days, and although weak and ill at the end of 2013, he was insistent that he would complete his teaching responsibilities through the end of the academic period, both in the Basic Program and at Loyola. In December he took a leave of absence from his teaching responsibilities.[14]

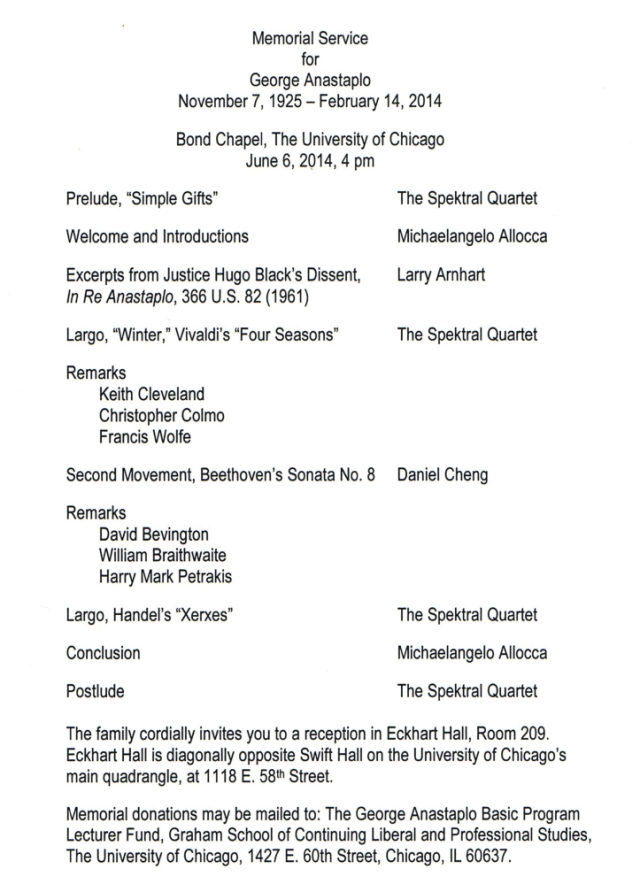

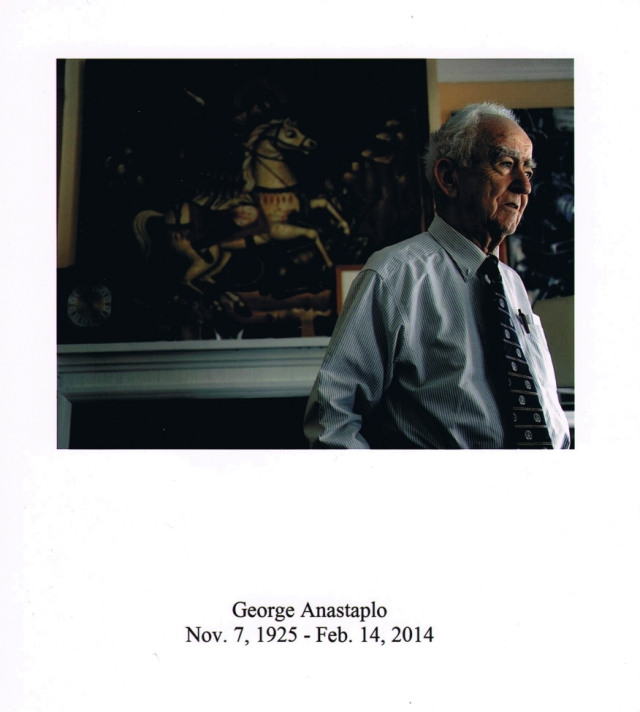

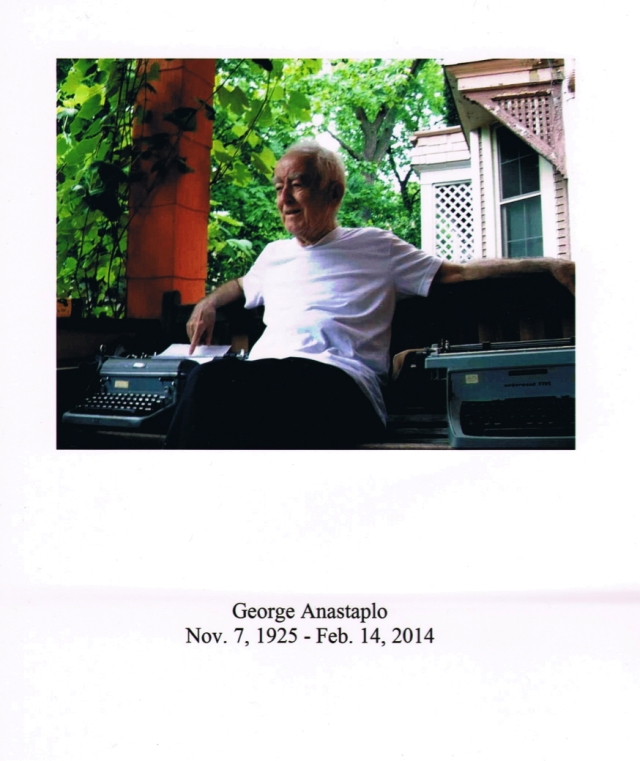

George Anastaplo died on February 14, 2014, and a memorial service was held on the campus of the University of Chicago, at Bond Chapel on June 6 of that year. It was impressive to see the number of people who attended the service, from so many different disciplines and backgrounds, all brought together by their connection to him. During his lifetime he was always making introductions among people he thought should know each other, and many of us at the memorial service did in fact know each other precisely because he had fostered those relationships. He was eulogized by colleagues, many of whom were former students or instructors from the Basic Program, Dominican University, and Loyola.

Of course, we were all lifelong students of George Anastaplo. He was always quick to invite one to sit in on a class or a lecture he was giving. No written communication or holiday card went unanswered, and he always included something he had recently written.

Throughout his life George Anastaplo shared his thoughts with others in a vast amount of writing on an immense number of topics. In addition to his blog at http://www.anastaplo.wordpress.com (a later form of publication for his essays), he authored twenty-one books, well over twenty book-length articles, numerous eulogies, and frequent letters to the editor. His final book, Reflections on War and Peace and the Constitution, was the sixth in a projected series of ten volumes of Reflections. The remaining volumes, the contents of which were already in progress, reflect his continuing curiosity about so many issues and had been preliminarily titled Reflections on Race Relations and the Constitution; Reflections on Crime, Character, and the Constitution; Reflections on Property, Taxes, and the Constitution; and Reflections on Habeas Corpus, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution. Although we have now lost the give-and-take of conversation with George Anastaplo, thanks to his profound and prolific writings, we can all continue to be his students.

[1] Many of the important events of Anastaplo’s life are touched upon by him in his 2004 preface to The Constitutionalist: Notes on the First Amendment (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2005).

[2] See the dedication to Anastaplo’s book Human Being and Citizen: Essays on Virtue, Freedom and the Common Good (Chicago: Swallow Press, 1975), which reads, “To My Parents, who discovered as Immigrants from Greece how difficult it is for one to become a Human Being where one is not born a Citizen.”

[3] When asked why he had decided to go to the University of Chicago, his only explanation (at least to some of us) was that someone had told him that it was a good school.

[4] Asked why he had decided to study law, Anastaplo’s answer was similar: someone had told him that he should study law.

[5] Chance is readily acknowledged by Anastaplo as an important and pervasive element in the unfolding of circumstances of great significance.

[6] A time, as Anastaplo puts it, “when so many of my fellow citizens were not altogether unwilling prisoners of the Cold War,” Constitutionalist, 333.

[7] 3 Ill. 2d 471, 121. N.E. 2d 826 (1954).

[8] Despite this decision, the committee’s 1959 report noted, “From the character affidavits and reference letters which have been submitted to us, it would appear that the applicant is well regarded by his academic associates, by professors who had taught him in school and by members of the Bar who know him personally. We have not been supplied with any information by any third party which is derogatory to Anastaplo’s character or general reputation. We have received no information from any outside source which would cast any doubt on applicant’s loyalty or which would tend to connect him in any manner with any subversive group.” Majority Report of Committee on Character and Fitness for the First Appellate Court District of Illinois, 1959, in Constitutionalist, 350.

[9] In re Anastaplo, 366 U.S. 82, 97 (1961).

[10] Thus, the dedication in his book On Trial: From Adam and Eve to O.J. Simpson (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2004) reads, “To the Memory of my Law School teachers (1948–1951) who, with a few noble exceptions, preached (and hence taught) far better than they could practice.”

[11] Constitutionalist, xxix.

[12] For a description of this incident, see Constitutionalist, 338–40.

[13] He had decided to teach all of Shakespeare’s plays, in chronological order, during that quarter and the anticipated two subsequent quarters. The class was completely subscribed, and Anastaplo waived the limits on the class size.

[14] On May 16, 2014, the students of the graduating class at Loyola elected him “professor of the year,” although he had taught during only one semester of that academic year.