George Anastaplo

The Declaration of Independence is important, of course, for the arguments it makes supporting the decision announced by delegates from thirteen British Colonies gathered in Philadelphia in July 1776. Their action itself, revolutionary in its scope, is what must have been most critical to both participants and observers. But it was an Action guided and reinforced by an Argument.

It is a remarkably disciplined Argument that drew upon centuries of deliberations and measures among the English-speaking peoples on both sides on the Atlantic Ocean. Two millennia of philosophical and theological speculations were also drawn on. It can still be wondered. of course. how coherent the overall understanding was that was relied on by Citizens at Large in the thirteen Colonies.

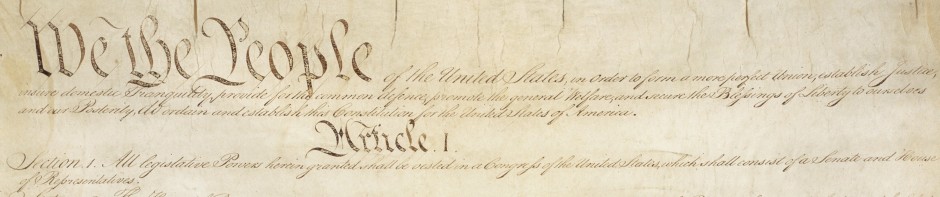

The Declaration itself has long had an iconic status in this Country. It is the first of the “Organic Laws of the United States” collected early on in our statute books. It can be reassuring to notice that it is a remarkably well-crafted instrument, with an integrity in its construction that both invites and rewards examination.

I.

The most familiar part of the document is its opening. The principles drawn on are set forth in eloquent terms that invite repeated recollection, Leo Strauss, at the outset of his 1953 Natural Right and History volume, could say of the We hold these Truths” sentence in the Declaration.

[This] passage has frequently been quoted, but, by its weight and its elevation, it is made immune to the degrading effects of the excessive familiarity which breeds contempt and of misuse which breeds disgust.

Mr. Strauss could end his 1953 volume with the observation (adapted here to our immediate concerns on this occasion):

The quarrel between the ancients and the moderns concerns eventually, and perhaps even from the beginning, the status of “individuality.” [Anyone] deeply imbued with the spirit of “sound antiquity” [would not] allow the concern with individuality to overpower the concern with virtue.

No argument (it seems to have been assumed in 1776) needs to be provided to support principles invoked at the outset of the Declaration. They are proclaimed to be –self-evident” truths. The ends of government are recalled — and –whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect [secure] their Safety and Happiness.”

The abuses that have moved these Thirteen Colonies “to alter their former Systems of Government” are thereafter provided in considerable detail. That detail, typically omitted when the Declaration is drawn on for public celebrations, can be most instructive when studied with the care it invites and deserves. The litany of abuses is introduced in this fashion:

The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World.

III.

Those are three sets of complaints with respect to “the repeated Injuries and Usurpations” emanating from “–the present King of Great-Britain.” The list begins prosaically. Much is made at its outset of the denial of government for the Colonists.

Thus, it is assumed that government is needed. No State of Nature is looked to as an alternative. In this (as in other ways), the English-speaking students of government deviated significantly from some of their Continental counterparts.

Not only had governmental services been systematically denied but there had also been a determined interference with the efforts made to arrange migration to these States. In various ways, that is, the routine functions of the Colonial legislatures, executives, and judiciary had been woefully interfered with. Thus, the account of grievances has the British government itself in effect “rebelling,” in that it had systematically denied the Colonists the governments they needed and deserved.

IV.

This, then, is the first of the three sets of grievances, the failure to permit the necessary governmental activities in the Colonies. The third set of grievances emphasizes the oppressive exercises of governmental power that the Colonists have had to endure for some years. This set is introduced with the complaint, “He [the present King of Great-Britain] has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.”

The list that follows recalls violent deeds that should move decent observers everywhere, no matter what form of government they may prefer. Thus, it is recalled, “[The King] has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People.” Indeed, it could well seem to independent observers everywhere that the British government had in effect given up any claim to ruling people treated in this fashion.

It is this vivid recollection of physically-destructive measures that leads immediately to the insistence that these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, free and Independent States.” So destructive are these measures that Peoples and Governments everywhere should be able to support this move to independence, whatever reservations they may have about some of the principles that have been invoked. A sense of humanity, worldwide, is thus appealed to.

V.

We have noticed that the three sets of grievances, suffered at the hands of “the present King of Great-Britain,” begins with complaints about denial of government. We have also noticed that they conclude with complaints about barbaric deeds for which the British King is considered responsible. The central set of grievances is distinctive in a critical respect, being introduced with the observation that “[The King] has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation…”

Nine such instances are listed, beginning with “quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us” and ending with “suspending our own Legislatures…” Central to this inventory are three complaints:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many Cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences.

These may well have been among the most troubling complaints that the Colonists had voiced for a generation.

Even so, these complaints are only indirectly leveled against the Parliament (the “others-that the King had “combined with”), even though that body had really been primarily responsible for them. It was rhetorically (and otherwise) important that the King remain the primary target dealt with in this document. After all, when this conflict ends, these rebels plan to have legislatures of their own but no kings.

VI.

The “imposing Taxes on us without [their] Consent” may have been the dominant grievance rhetorically. The Stamp Act (however minor it may have really been overall) could be readily condemned. We can be reminded by such resistance of the importance of property and its protected development for these ambitious North Americans.

Appeals are made in the Declaration of Independence to “a candid World.” Were not peoples elsewhere (and especially in France) more apt to be moved by grievances that embrace anarchy (no government) and systematic violence than by supposed abuses of British constitutional standards? Indeed, some of the governments friendly to the Colonists could not have been eager to have their own peoples hear celebrations of the principles implicit in Anglo-American constitutionalism.

We should be reminded here that those issuing the Declaration of Independence do look like legislators. They may have been “naturally” more inclined to attack royalty (or executive usurpation) than any legislative misconduct. After all, the legislatures that would become critical in the years immediately ahead among them would be routinely (almost “naturally–) guided in their operations by the rules and precedents of British Parliaments.

VII.

It must have been partly a matter of chance what grievances were recalled on this occasion. The lists of grievances may have depended in part for who happened to be present from the various Colonies. Also to be taken into account (we have noticed) must have been concerns about what might (or might not) appeal to potentially influential observers in Europe and elsewhere.

But it does not seem to have been a matter of chance how the Declaration of Independence was organized. Delegates may well have come with drafts to be drawn on. The most notable was the draft developed by Thomas Jefferson, a draft that the Philadelphia assembly moderated in various ways.

The overall organization of the final draft is remarkably disciplined. This is evident in what we have noticed about how the misconduct of the Parliament for a generation was played down. The villain of this document, we have also noticed, was “the present King of Great Britain,” someone who had been determined to establish “an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

VIII.

But, the Declaration implicitly recognizes, not all tyrannies are equal. Consider the concluding grievances listed on this occasion:

He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction of all Ages. Sexes, and Conditions.

Forgotten here, it seems, was the use that the Colonists themselves had made (as allies of the British) of such Tribes during the French and Indian War of the preceding generation.

Also forgotten, it may seem, is the insistence at the outset of the Declaration of Independence “that all Men are created equal.” All, it is further insisted, are entitled to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” English critics of the Declaration of Independence could even reply that their rebellious Colonists were being hypocritical when they complained about the Domestic Insurrections” (that is. the emancipation of slaves) that the British forces were resorting to in their effort to suppress rebellious Colonists.

Indeed, a critic today of the authors of the Declaration of Independence may even be tempted to find understandable what the British authorities may have been doing in promoting what is condemned in the Declaration as “domestic Insurrections.” Such a critic might even venture to suggest that what the British were doing in the 1770s about slaves held by rebels is what Abraham Lincoln did with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862-1863. Of course, Lincoln had always made much of the insistence in the Declaration that “all Men are created equal.”

IX.

The astuteness of the mature Lincoln can be recognized in how he organized his most enduring statements. Also quite remarkable is the astuteness evident in the organization of the Declaration of the Independence. That is, a highly disciplined arrangement could be developed on behalf of an assembly with divergent talents, presuppositions and interests.

Particularly noteworthy in the Declaration of Independence, we have noticed, is the craft (if not even the craftiness) that plays down (if it does not even effectively conceal for the moment) the role that the British Parliament had played in the development of the Crisis being addressed. Are there in the Sources available any indications of how this was done and by whom? And are there in the bountiful scholarly literature about the Founding Period informed investigations of these developments?

We have been concerned, in short, to notice the craftsmanship drawn on by the authors of the Declaration of independence. It is such craftsmanship that is evident as well thereafter in the Constitution of 1787. That, too, is a seminal document that is no longer read with the discipline that it both requires and rewards, something that can perhaps be expected whenever more and more seems to be made of an undisciplined “individuality.”

______________________

These remarks were prepared for George Anastaplo’s Constitutional Law Seminar, Loyola University of Chicago School of Law, November 25, 2013. This essay should be included in his Reflections on Property, Taxes, and the Constitution (the ninth volume of a contemplated ten-volume Reflections series, five volumes of which have been published as of 2013).